Christmas here is not of much importance, but the New Year is duly celebrated with much festivity. It seems to be the custom of all customs to pay up all debts at the end of the year, and to begin the next owing no man anything. The Chinese I believe put a notice on their dues that they have paid all debts, so that the gods, or demons, will pass them by when looking for a place to do some mischief.

The Japanese make a gala time of it from December 11th. For about a month the children wear their best clothes, and are not molested if they get them soiled. Everybody takes a holiday for two weeks and dresses in the best they can afford.

I am far away – and am only happy when studying. However, I don’t stay happy long, for the language is perplexing. The teacher says "Meshi means rice". All right. Then I ask him in Japanese "Do you like meshi?". And I find out that I have been very impolite – anybody else’s rice is gohan. The person speaking eats meshi. Supposing that children eat meshi, one finds that he has again erred – children eat mami. Supposing that I will not make a mistake when I speak only of things irrespective of persons, I say "Meshi grows in the fields". He replies "No – meshi does not. It is ine when growing. Ine grows in the field". And finally I ask if the storekeeper sells meshi and find that meshi means cooked rice only – the storekeeper sells kome.

It is strange, and I cannot understand it nor is it probable that I will, but when I walk along their streets it is incomprehensible to me how so many years could have gone by, and yet this one fact, the greatest in the world’s history, and the one which most concerns the inhabitants of the earth, still remains unknown, or not appreciated, or not understood, by 999-1000 of many thousands of these people – yes, civilized people – I meet in the streets. They are not civilized as a western man counts civilization with all its modern inventions and appliances, for expectations in business and comforts in life – but they have civilization, and are far more civil and polite than the modern, hustling businessmen in America. But they are also ignorant, and therefore have a pride which nothing can conquer save education.

Here only a rich man, an ambassador or something like that, has a horse-drawn vehicle, and then he has a couple of coachmen who do the driving for him, while another perhaps rides horseback, or runs in front to warn the crowd of the approach of trotting horses. All the horse-drawn vehicles in Japan are made very low. The wheels are very small, but strong-looking men are the usual beasts of burden and if you happen to see one of these scraggy little ponies pulling a load, it is generally on a two-wheeled flat-bottomed dray – or balancing cart – while the man leads the horse.

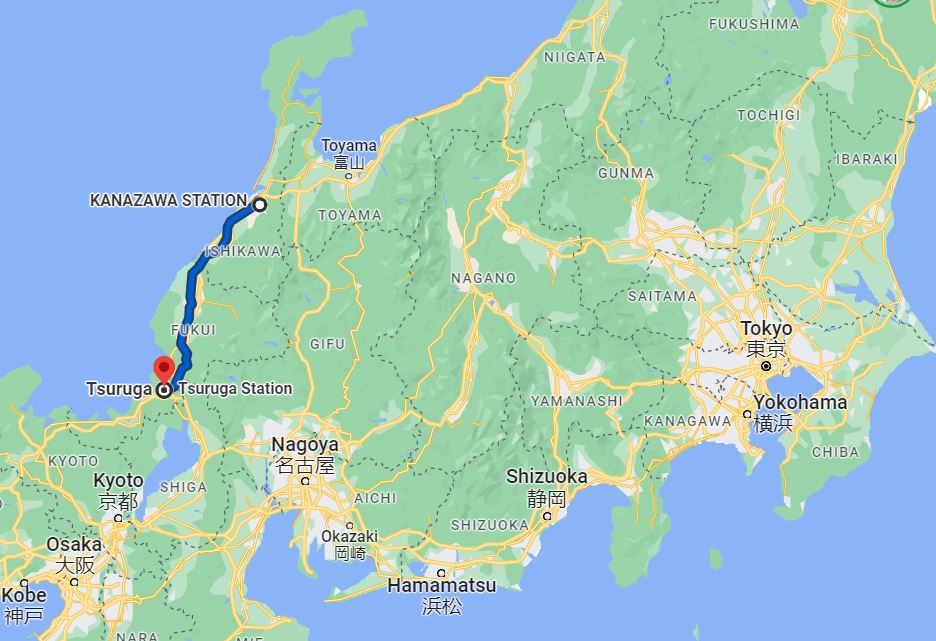

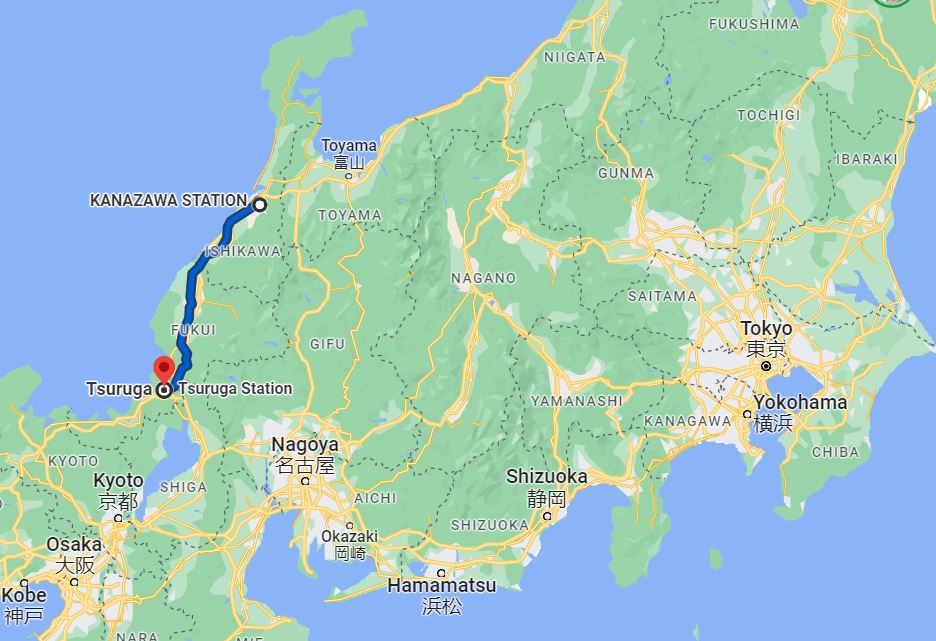

I am here in Tsuruga in a Japanese hotel, having arrived a few hours ago from Kanazawa after a ride of five hours on the small train which they have in this country. It must be 120 miles to Kanazawa. The Bishop has put this place under my charge – and a hard time I shall have, not knowing the language. We have a catechist here, a Mr. Ota, who was once a Buddhist priest, and he is a resident and keeps up the small church by preaching. I think I am at present the only foreigner in this town, but don’t fear – they are very peaceful people. A foreign man in this country is no longer an object of any great curiosity, for the Japanese officials all wear "yo fu hu" (foreign clothes) but a foreign woman is always the object of great admiration, and has a troop following her everywhere she goes.

I find writing to you here a difficult job, as I am sitting on the floor. This table is just the height of my big toe when I put my heel on the floor with my toes up. It is a regular writing table, and has "fude & sumi" ready for use, but I prefer my pen. The Japanese sit on their heels, which I cannot stand for long, so I have sat down Turkish fashion, and find my feet in my way. It is just five o’clock and one of the many temple bells is peeling forth the hour. It is a heathenish land certainly, where you hear no church bells and see no tall steeples with crosses on them.

But I must say on behalf of the Buddhists that they have chosen very beautiful tones for their bells – sometimes the sound grates me surely, and makes shivers run, but I am getting used to it and forget the bell is a heathen temple bell. It sounds so deep and clear. At first it seemed to me, when I heard that big bell at Nara ring out slowly and surely, steadily and gloomily, it seemed that I was hearing the death knell of all that was good, righteous and holy. I wanted to pack my case and go away. But now I almost forget the religious significance (and I believe there is none, for the religion of Buddhism is gone) and I admire the skillful harmony of tone with the Japanese scenery.

They bring wooden clogs (geta) and leave them at the door. Now it would be very rude to make them walk in their clean tabi (a sort of sock made of white stuff with a separate apartment for the big toe) on a place where we walk without shoes even tho’ it is a very clean floor, so we have provided slippers for our guests; something they like. But which I never can keep on which has only one toe but no heel. If you walk into a Japanese house with your shoes on, the Japanese would have very much the same feeling you would have if somebody came into your parlor and walked on your chairs and sofas and on your bed with his shoes. No matter how clean the shoes, it would not be relished by the owner.

We are going calling in a few hours this afternoon and I shall carry a shoehorn to enable me to replace my shoes. Of course everywhere we go we drink a cup (or more) of tea and eat a cake. One afternoon I drank 14 cups of tea, but they were small ones. Japanese tea cups are small round things with no handles – all the ones with handles are made for foreigners to use. It is also very rude not to drink your tea and eat your cake. It has to be done, it’s something as necessary as a handshake at home. On one occasion the host brought me the cake I had left half-eaten. If you don’t eat it you must fold it up very carefully and carry it away with you, not leaving a crumb. I once heard of a man who at a foreign dinner helped himself to half the butter, not knowing what it was, and then because he could not eat it all, wrapped up what he left and carried it off.

Right now we are very busy starting our school work in connection with the church here. We are opening a sewing school for girls which Miss Sutton and her Bible woman Mrs. Machikawa are going to run, and in the rooms below the church (the church is upstairs) we are teaching English and the Bible in English. This has to be done to attract people to you, and then the contact with you will give them some insight into your desires for them, and what Christianity is. They do not come to hear preaching, unless there is some special attraction, and street preaching has long ago been given up in China and Japan. Strange to say we need more work among the women than among the men.

It is impossible for a man to [be unaffected by?] the dark, gloomy forests with big crooked trees in them, covered with green moss, and filled with moats and scum and dark things, waterfowl, and rocks and ponds and fish and bronze storks and wooden bridges and stone bridges and crooked pines, and torn and thatched roofs, and bamboo and muddy rice fields: this is Japan.

I have had my supper and did not move off my mat. The servant brought it in on a little four-legged square table almost as high as this one. There were four bowls on it, and one bowl was for rice. This bowl you eat from with chopsticks; the other bowls had fish soup, fish cooked, and fish raw and some relishes of some vegetable kind, which I did not relish.

No – I don’t have to go bare-footed in my own house, but it would be more comfortable to do so, for the floors are so soft. As furniture is very hard on a soft mat, we had to make runners on our chair to keep the legs from cutting holes in the mats, and under the bed legs there are just square blocks of wood.

We wear shoes in our own house, but visitors who are [usually?] women [do not?], and we have to depend on our native Bible women. Our ordinary congregation consists of four women and twenty men, just the reverse in America.

Tucker and I have just had a long discussion about the scarceness of missionaries in our several dioceses. Tucker belongs to the Tokyo diocese, and claims for it the greatest need. There are however in this diocese (Kyoto) 32 towns of over 10,000 people which have no clergyman or layman, or catechist, or bible teacher, of our Church. Some time I shall make a map of these four provinces in which Welborn and I are placed, and send it home. The names of these provinces are Etchen, Etchizen, Noto, and Kaga.

Tucker and I will soon take a trip up one of the high mountains in this neighborhood. Mount Nakusan or rather Hakusan – san means mount while haku means white, for snow is on it. It is 8,900 ft high, and only 43 miles off. There are six others much higher but further off, one of which is 10,500 ft high.